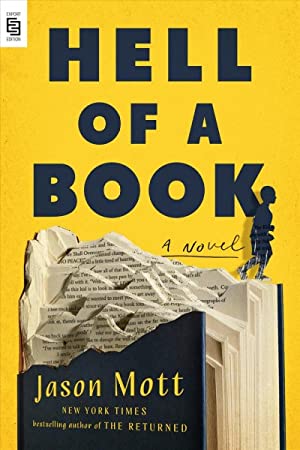

Hell of a Book, a novel by Jason Mott, is about the danger black American men are in when they are seen by white people in this country, and how black parents might want to teach their sons to be invisible in order to keep them safe.

To explore this idea, Mott contrasts the visibility of three characters: The narrator, an author on a book tour (we are told he is black in the book jacket text, but I didn’t notice that description of him in the beginning), a young boy nicknamed Soot (the one whose parents want him to be invisible) who is very dark-skinned, and another character, the boy, who may or may not be real and who may or may not be the ghost of a young black boy who was recently shot by police (I am assuming this, as I am not far into the novel and during the first scene in which he appears to the author, the tv is telling the story of this murdered child). (I have a guess about who the boy turns out to be, but my guess has not yet been confirmed.)

Recently, someone asked me to stop talking about myself. I know that might sound like I talk about myself a lot–and I do–but this was someone who should not have said that to me. I’ve known this person a very long time and I’ve always wondered why he always rolls his eyes when I speak (this is not my son, by the way, this is very much an “adult”). He does not want to know me. It was a shocking thing to hear, but it was validating. Now I understand.

Beginning the novel a day or two after this was said made me consider the contradiction of invisibility (if you can’t be seen, you can’t be hurt) and its damage (do you exist? do you matter? does anyone care about you?).

Of course, I understand entirely how the parents of a black boy in the United States would want him to be invisible in order to be safe. The system is wrong, but in the face of a broken system, a parent’s first priority is always their child’s safety. Only the bravest parents would want their child to put himself out there to change the system and be seen.

However, this doesn’t make any sense because loving parents want to see and know their children and they want their children to be seen and known by the world. Loving parents are delighted by their children. Honestly, one of my favorite memories of James is his voice, before he actually learned to talk, when he would babble in his car seat when I picked him up from daycare, telling me about his day. In fact, just yesterday, he was playing video games with his friends after working outside all day in the heatwave and I could hear his laughter. It was the best part of my day (and probably his, based on the long and loud laughter). James’ voice is my favorite sound and I always want to know what he thinks and feels.

Mott’s exploration of this contradiction is meaningful because of his honesty in confronting this upsetting challenge. He reminds his reader through a compelling story that now is the time to listen to the voices in the United States that have long been silenced and to see the people in this country who have long been invisible.

“She wanted to have a child that could exist beyond it all. She wanted a child that could be free from it. A child that could never get shot. A child that didn’t have to be afraid. A child that she didn’t have to be afraid for because, at any moment, they could just disappear.”

Leave a comment